This article is about Log Structured Merge (LSM) trees data stores.

Intro

I have always been fascinated by the tech underlying distributed databases such as Cassandra and Bigtable. A few years ago, I read the BigTable paper and its Sorted String Table (SST) building block. I also started poking around the leveldb code base - a popular key value store implementation based on BigTable internals.

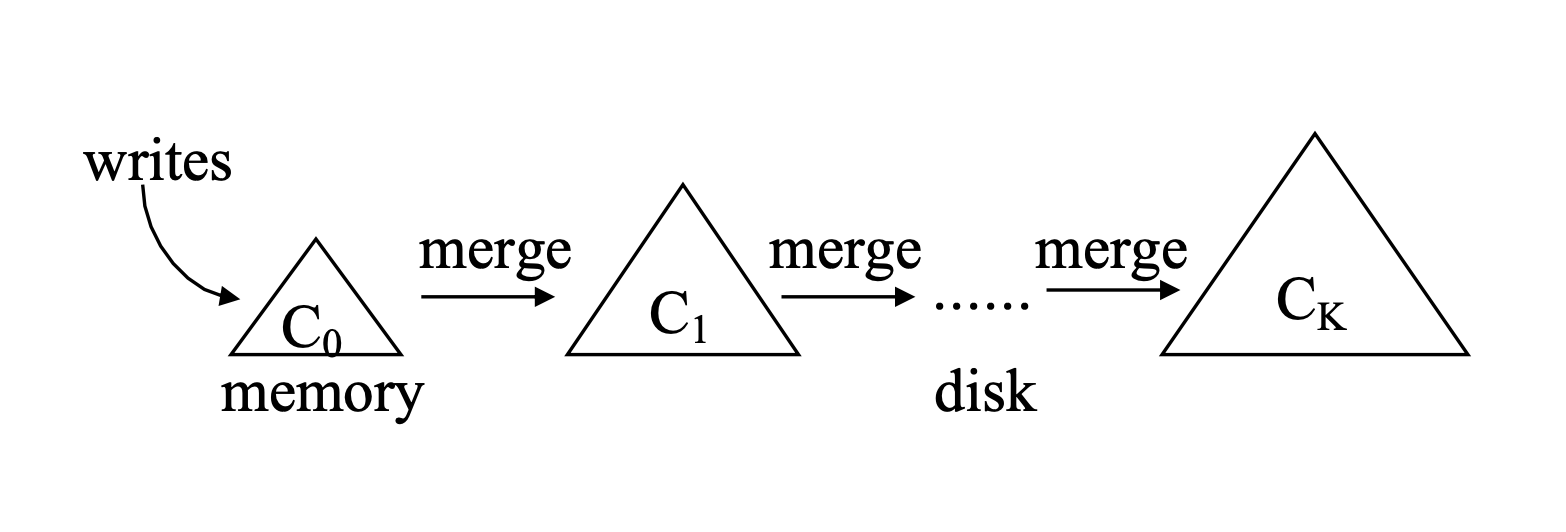

At their core, LSM data stores present a simple idea. They have a small in-memory component and a large on-disk component. The purpose of in-memory component is to buffer writes and achieve a high write throughput. Data is initially written in memory and late synced to disk when the in-memory component becomes full. This idea is based on the LSM tree paper from the 90s. In LSM tree lingo, the in-memory component is called the memtable and is usually implemented using a skip list or a B+ tree. Its counterpart on disk is usually implemented as a Sorted String Table (SSTable). The SSTable name alludes to the fact that LSM-trees are key-ordered stores. The ordering is a crucial design choice in-order to provide good read performance and make data organization easier.

image from paper

image from paper

There are several reasons why the LSM data structure underpins the key value stores:

- Write performance

The memtable acts as a buffer, ensuring that writes never have to block waiting for disk. The writes get written to memory and are later synced to disk when the memtable is full. This write performance is desirable where there are spikes in write loads. The memtable smooths them out, ensuring a consistent write performance.

- Solid State Drives

Since writes are buffered in memory, they get written out sequentially to disk. Sequential writing fits well with SSDs. Flash based SSDs usually implement a log-structured flash translation layer to minimize their erase/program cycles; all updates are written to disk sequentially to an append only log structure and existing data is never overwritten.

The flip side of having great write performance is read performance isn't as fast. As the on-disk SSTables, produced every time a memtable is synced to disk, accumulates over time, the query performance of the LSM-tree degrades since more components need to queried. To address this, SSTables are merged; this is known as compaction.

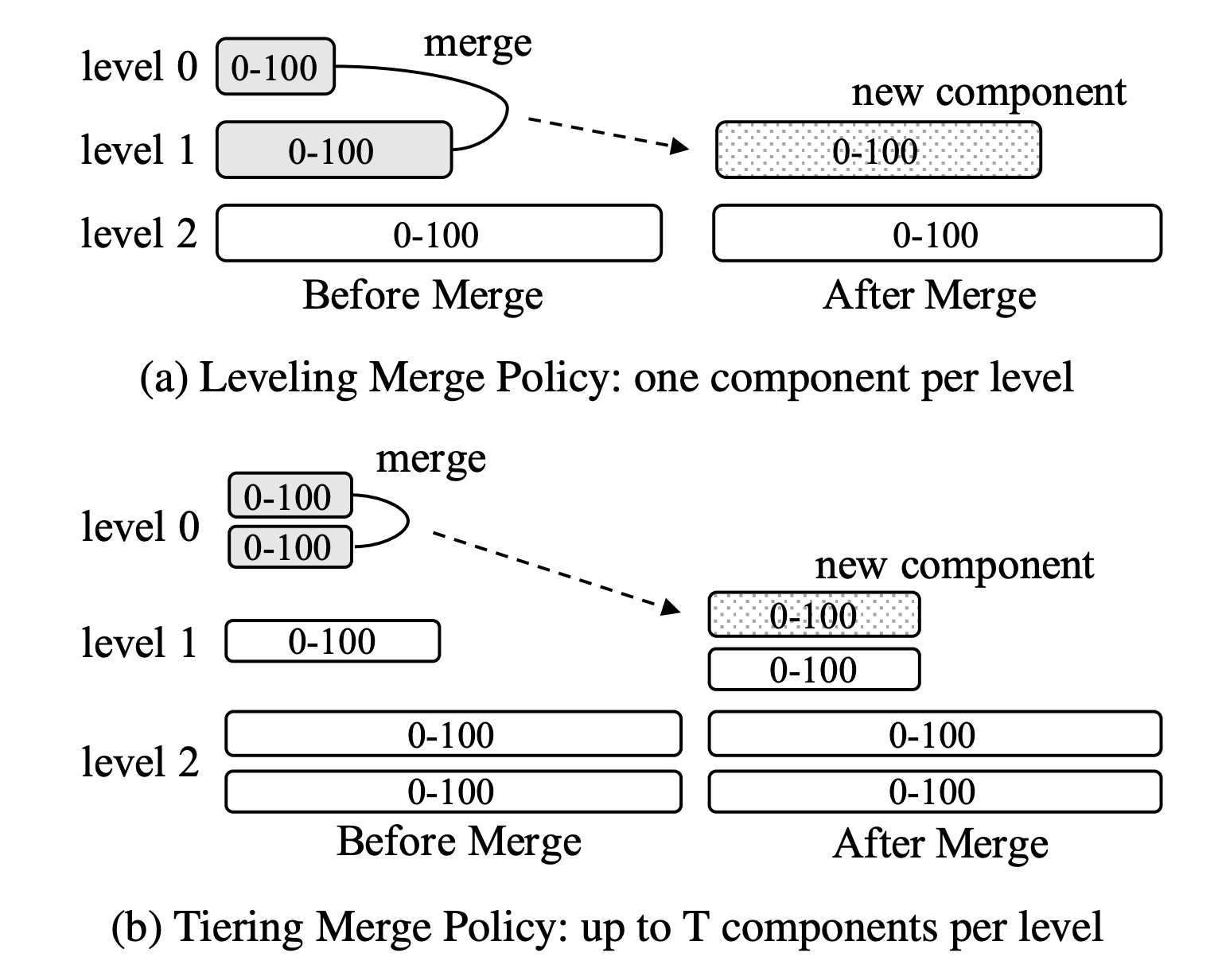

There are two main compaction strategies used in practice:

- Leveled

SSTables are organized logically into levels based on a size ratio. Each level can at most have a single SSTable. Level 0 contains the flushed memtables and can have more than one table. The level 0 SSTables get merged into the level 1 table until it exceeds a certain size, and then it is merged into the level 2 SSTable and so on...

Having a single SSTable per level improves reads since there are fewer tables to scan. However, the merge frequency is high.

- Size-tiered

Similar to the leveled strategy, except that there can be multiple SSTables on each level. When the number of SSTables on a certain level reaches the level's size limit, the SSTables are merged together as a new SSTable on the next level. This strategy is write optimized as merge frequency is lower but reads become slower since more tables need to be scanned.

image from paper

image from paper

Ghala DB

I wanted to deeply understand the nitty-gritty details that went into LSM stores, so I wrote one. I had read the wisckey paper and liked their idea on separating keys and values to minimize I/O amplification, and so I decided to incorporate this idea in my implementation.

GhalaDB is a simple LSM tree key value store written in Rust. It's simple in the sense that it does not implement a barrage of features found on fully fledged systems such as leveldb. There's no data corruption checks, no versioning, no ranged queries. What it implements though is a proper key-value store API, keys and values separation and an online data compaction scheme. Just the basic features for me to get a good grasp of how these systems are implemented.

GhalaDB has a memtable implemented using the B-Tree Map from the Rust standard library. The memtable stores the keys and their associated data pointer. The data pointer keeps information about where to read the key's value.

pub struct DataPtr {

/// The value log number

pub vlog: VlogNum,

/// Data offset in the value log file.

pub offset: u64,

/// Data size

pub len: DataEntrySz,

/// Data compression flag.

pub compressed: bool,

}

On disk, GhalaDB maintains a values log that sequentially stores data pointer alongside their data entries. A data entry is a key and value pair. The values log has a configured max size, and a new values log is created when the current one reaches the max size.

pub struct DataEntry {

pub key: Bytes,

pub val: Bytes,

}

The on-disk data layout on the vlog is:

| START |

|---|

| DataPtr1 <21 bytes> |

| DataEntry1 |

| DataPtr2 <21 bytes> |

| DataEntry2 |

| . |

| . |

| . |

| . |

| DataPtrN <21 bytes> |

| DataEntryN |

| END |

The Write Path

- Create a data entry (key-value pair)

- Compute the data entry size on disk.

- Generate a data pointer using a computed offset.

- Write the data pointer and data entry to the current write-active values log.

- Store the key and the data pointer in the in-memory memtable.

- Return OK.

The Read Path

- Lookup the key in the memtable and get its data pointer.

- Read the data entry from the values log.

- Return the value.

Compaction

Compaction is online and happens on the write path. If there is an old values log that needs to be garbage collected, data entries from this vlog are fetched and insert to the currently write-active vlog. This process is akin to garbage collection in log structured filesystems.

To avoid write stalls, the compaction is incremental and only progresses a tiny bit for each write request. The garbage collector scan the vlog and returns any live data it finds, which is then re-inserted to the active vlog.

pub(crate) struct GarbageCollector {

vnum: VlogNum,

vlog_iter: VlogReader,

}

impl GarbageCollector {

pub fn new(vnum: VlogNum, path: &Path) -> GhalaDbResult<Self> {

debug!("GarbageCollector::new vlog: {vnum} at: {path:?}");

let vlog_iter = VlogReader::from_path(path)?;

Ok(Self { vnum, vlog_iter })

}

pub fn sweep(&mut self, keys: &mut Keys) -> GhalaDbResult<Option<DataEntry>> {

trace!("GarbageCollector::sweep");

loop {

match self.vlog_iter.next_entry()? {

None => return Ok(None),

Some((dp, de)) => {

match keys.get(&de.key) {

None => continue,

Some(cur_dp) => {

if cur_dp == dp {

// data is live and should move to tail

return Ok(Some(de));

} else {

continue;

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

Outro

If you are interested in looking at the entire code, it is available on Github.